I’m currently reading Jenny Odell’s Saving Time, a book that sucks you in and holds up a mirror to some of the weird and wonky ways we meatsacks conceive of time.

Consider everyday phrases such as “I don’t have enough time” or “I want to spend more time with you” or “You should invest your time elsewhere”. The common denominator, of course, is that these are all metaphorically part of the same language family: that of labour and money.

Writing nearly half a century ago, the (ex-communicated) Catholic theologian and social critic Ivan Illych had this to say about how money influences our perception of time:

How might we think and talk about time if the world were organized differently? What new linguistic mappings would emerge?

In Saving Time, Odell makes the case that the origins of how we think about time are often rooted in violence. “Clocks arrived as tools of domination.” In one funny but sad passage, she quotes the daughter in-law of a British missionary living in South Africa in 1861: “You must know that today we have unpacked our clock and we seem a little more civilized. For some months we have lived without a timepiece. John’s chronometer and my watch have failed, and we have left time and been launched into eternity. However, it is very pleasing to hear ‘tic tic tic’ and ‘ding ding.’”

Why does living outside of “clock-time” (which is really linear, labour-time) feel like eternity?

And what happens when even clock time ceases to make sense?

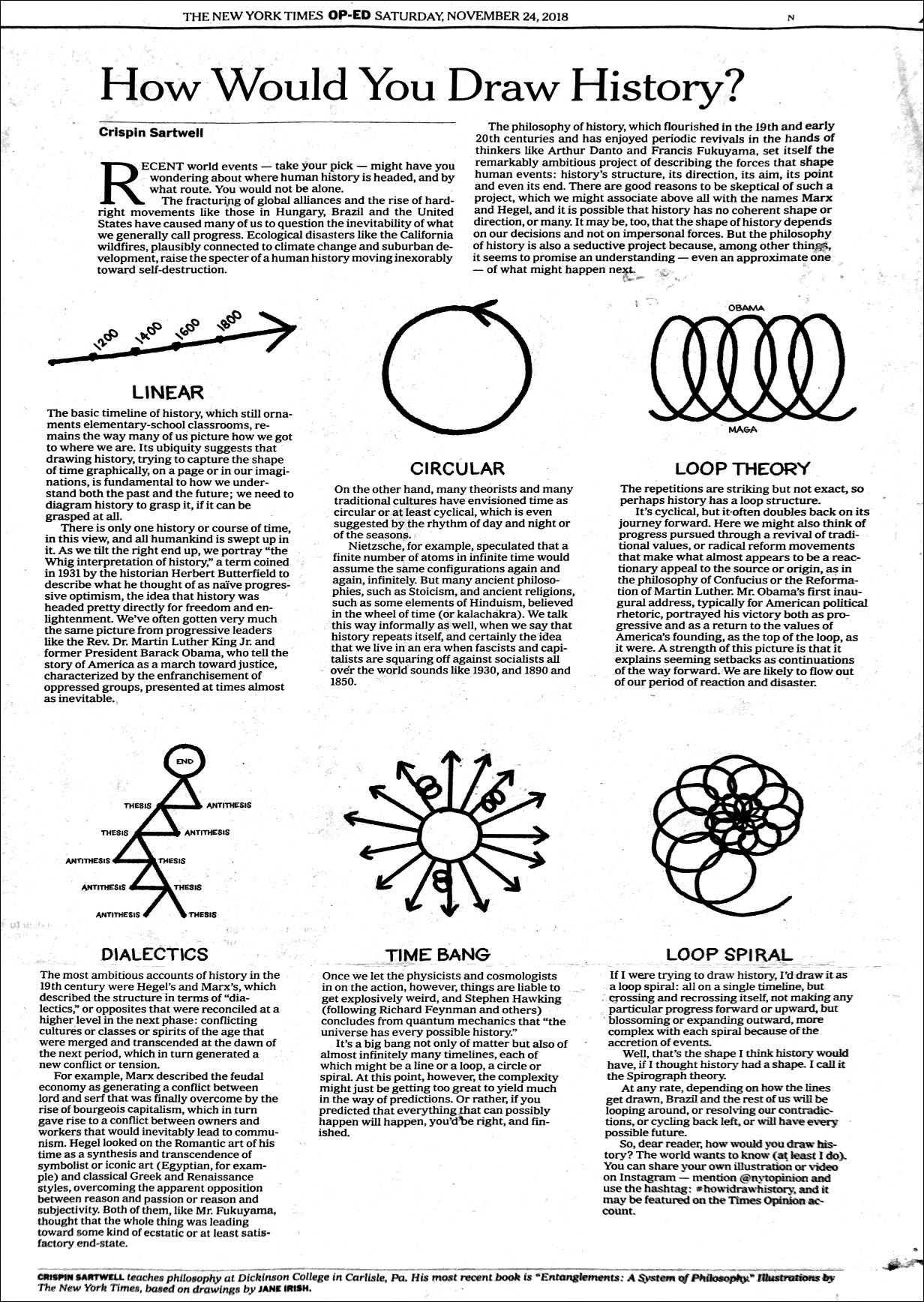

Odell writes about the cognitive dissonance of trying to live in a world where we must contend with competing time scales. For example, consider the discomfort that exists between thinking about long, ambiguous timescales (like geological time in the context of climate change) and everyday clock time (like being late for work). One is stretchy and out of reach and makes us feel small. The other is discrete and staccato-like and demands immediate attention. There’s a fuzzy threshold at which units of standardization, like time, cease to make sense to the human mind. But that same mind likes to think that by universalizing a concept across both domains, it extends equal control.

There’s nothing wrong with building conceptual walls to make sense of the world (we do it with time, money and just about everything else). But we need to be more sensitive to what those fuzzy spaces do to us, because chances are we’re going to have to confront them more and more.

Maria Popova writes:

We spend our lives trying to discern where we end and the rest of the world begins. We snatch our freeze-frame of life from the simultaneity of existence by holding on to illusions of permanence, congruence, and linearity; of static selves and lives that unfold in sensical narratives. All the while, we mistake chance for choice, our labels and models of things for the things themselves, our records for our history. History is not what happened, but what survives the shipwrecks of judgment and chance.

We oscillate between living for the moment and trying to save the future. We are told to focus on the beauty of the present, but that we must start predicting and planning for said future lest we lose it. What joke is this? Speculative fiction like Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future is on the rise. Now, not only must we make sense of where we are, we must consume an infinite array of plausible trajectories, weigh up the pros and cons of each, and do our darn best to move the lever in that direction, all while smelling the flowers and practicing four-box breathwork on a Tuesday morning.

None of this is normal.

And perhaps that’s a good thing.

Books like Saving Time present arguments that might as well be extended to other conceptual norms we take for granted (ahem – money!) We’re invited to consider alternatives that make us uncomfortable, hopeful and curious all at once.

I’m using Non-linear time. Wasn’t an option.